What Is Heart Bypass Surgery?

Heart bypass surgery is when a surgeon takes blood vessels from another part of your body to go around, or bypass, a blocked artery. The result is that more blood and oxygen can flow to your heart again.

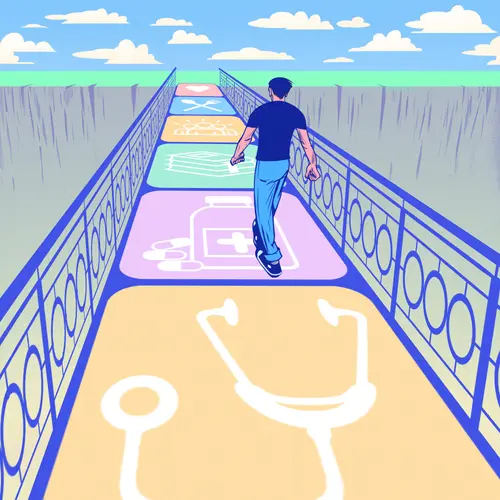

Imagine you’re on a highway. An accident causes traffic to pile up ahead. Emergency crews redirect cars around the congestion. Finally, you’re able to get back on the highway and the route is clear. Heart bypass surgery is similar.

It can help lower your risk for a heart attack and other problems. Once you recover, you’ll feel better and be able to get back to your regular activities.

Bypass surgery is also known as coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). It’s the most common type of open-heart surgery in the U.S. Most people have great results and live symptom-free for a decade or more.

You’ll still need a healthy diet, exercise, and probably medicine to prevent another blockage. But first, you’ll want to know what to expect from the surgery, how to prepare, what complications can happen, and what the recovery is like.

Why Do I Need Heart Bypass Surgery?

Bypass surgery treats symptoms of coronary artery disease. That happens when a waxy substance called plaque builds up inside the arteries in your heart and blocks blood and oxygen from reaching it.

Your doctor may suggest heart bypass surgery if:

- You have severe chest pain that your doctor thinks happens because several of the arteries that supply blood to your heart are blocked.

- At least one of your coronary arteries has disease that's causing your left ventricle -- the chamber that does most of your heart's blood pumping -- to not work as well as it should.

- There's a blockage in your left main coronary artery, which gives your left ventricle most of its blood.

- You've had other procedures, and either they haven't worked or your artery is narrow again.

- You have new blockages.

Coronary artery disease can lead to a heart attack. It can cause a blood clot to form and cut off blood flow. Bypass surgery can give your ticker a big health boost.

How Do You Prepare for Bypass Surgery?

Before your surgery, you’ll get blood tests, chest X-rays, and an electrocardiogram (EKG). Your doctor may also do an X-ray procedure called a coronary angiogram. It uses a special dye to show how the blood moves through your arteries.

Your doctor will also let you know if you need to make any changes to your diet or lifestyle before the surgery and make any changes to medicines you take. Also tell your doctor about any vitamins and supplements you take, even if they are natural, in case they could affect your risk of bleeding.

You’ll also need to make plans for recovery after your surgery.

What Happens During Heart Bypass Surgery?

You’ll be asleep the whole time. Most operations take between 3 and 6 hours. A breathing tube goes in your mouth. It's attached to a ventilator, which will breathe for you during the procedure and right afterward.

A surgeon makes a long cut down the middle of your chest. Then they'll spread your rib cage open so that they can reach your heart.

Your surgical team will use medication to temporarily stop your heart. A machine called a heart-lung machine will keep blood and oxygen flowing through your body while your heart isn't beating.

Then the surgeon will remove a blood vessel, called a graft, from another part of your body, like your chest, leg, or arm. They'll attach one end of it to your aorta, a large artery that comes out of your heart. Then, they'll the other end to an artery below the blockage.

The graft creates a new route for blood to travel to your heart. If you have multiple blockages, your surgeon may do more bypass procedures during the same surgery (double bypass, triple bypass, etc.).

In some cases, the surgeon may not need to stop your heart. These are called “off-pump” procedures. Others need only tiny cuts. These are called “keyhole” procedures.

Some surgeries rely on the help of robotic devices. Your surgeon will recommend the best operation for you.

What Happens After Heart Bypass Surgery?

You’ll wake up in an intensive care unit (ICU). The breathing tube will still be in your mouth. You won’t be able to talk, and you'll feel uncomfortable. Nurses will be there to help you. They’ll remove the tube after a few hours, when you can breathe on your own.

During the procedure, the medical team will probably have put a thin tube called a catheter into your bladder to collect urine. When you’re able to get up and use the bathroom on your own, they’ll remove it.

They also attached an IV line before the surgery to give you fluids and medications. You’ll get it removed once you’re able to eat and drink on your own and no longer need IV medications.

Fluids will build up around your heart after the procedure, so your doctor will put tubes into your chest. They’ll be there for 1 to 3 days after surgery to allow the fluid to drain.

You may feel soreness in your chest. You’ll have the most discomfort in the first 2 to 3 days after the procedure. You will probably get pain medicines for that.

You’ll also be hooked up to machines that monitor your vital signs -- like your heart rate and blood pressure -- around the clock.

You should be able to start walking 1 to 2 days after surgery. You’ll stay in the ICU for a few days before you're moved to a hospital room. You’ll stay there for 3 to 5 days before you go home.

What’s Recovery Like After Bypass Surgery?

It’s a gradual process. You may feel worse right after surgery than you did before. You might not be hungry and even be constipated for a few weeks after the surgery. You could have trouble sleeping while you’re in the hospital. If the surgeon takes out a piece of healthy vein from your leg, you may have some swelling there. This is normal.

Your body needs time to recover, but you’ll feel better each day. It'll take about 2 months for your body to feel better after surgery.

You’ll visit your doctor several times during the first few months to track your progress. Call them if your symptoms don’t improve or you’re feeling worse.

Talk with your doctor about the best time to return to your normal day-to-day activities. What's right for you will depend on a few things, including:

- Your overall health

- How many bypasses you've had

- Which types of activity you try

You'll need to ease back in. Some common plans include:

Driving. Usually 4 to 6 weeks, but you need to make sure your concentration is back before you get behind the wheel.

Housework. Take it slow. Start with the simple things you like to do and have your family help with the heavy stuff for a bit while you recover.

Sex. In most cases, you should be physically good to go in about 3 weeks. But you may lose interest in sex for a while after your surgery, so it could be as long as 3 months before you're ready to be intimate again.

Work. Apart from the physical requirements of your job, your concentration and confidence will have to come back. Most folks are able to resume light duty after about 6 weeks. You should be back to full strength after about 3 months.

Exercise. Your doctor may suggest something called cardiac rehabilitation. It's a customized, medically supervised exercise program. It also provides lifestyle education, which can include help with nutrition. Once the program is completed, you can work up to whatever fitness level you're comfortable with.

What Are the Risks of Heart Bypass Surgery?

All surgeries come with the chance of problems. Some include:

- Blood clots that can raise your chances of a stroke, a heart attack, or lung problems

- Fever

- Heart rhythm problems (arrhythmia)

- Kidney problems

- Infection and bleeding at the incision

- Memory loss and trouble thinking clearly

- Pain

- Reactions to anesthesia

- Stroke

- Pneumonia

- Problems breathing

Many things affect these risks, including your age, how many bypasses you get, and any other medical conditions you may have. You and your surgeon will discuss these before your operation.

Once you’ve recovered, your symptoms of angina will be gone or much better. You’ll be able to be more active, and you’ll have a lower risk of getting a heart attack. Best of all, the surgery can add years to your life.

What Are the Alternatives to Bypass Surgery?

There are a few less-invasive procedures your doctor could try instead of bypass surgery.

Angioplasty. A surgeon threads a deflated balloon attached to a special tube up to your coronary arteries. Once it's there, they inflate the balloon to widen your blocked areas. Most times, it happens in combination with the installation of something called a stent, a wire mesh tube that props your artery open.

There's also a version of angioplasty that, instead of a balloon, uses a laser to eliminate the plaque that clogs your arteries.

Minimally invasive heart surgery. A surgeon makes small incisions in your chest. Then, they attach veins from your leg or arteries from your chest to your heart, much like a traditional bypass surgery. In this case, though, your surgeon will put the instruments through the small incisions and use a video monitor as a guide to do the work. Unlike bypass surgery, your heart is still beating during this procedure.